On nonlinear recovery and trying to look forward

Western States is in five weeks. Suffice to say, I'm not where I'd planned to be.

In late March, when I wrote here last and had my swollen ankle propped up on couch cushions, I knew the weeks of rehab and recovery would be a mix of frustration, anxiety and uncertainty.

I knew I’d have to overhaul my training plan for Western States and reset my goals. Epic trail adventures in the lead-up to the last weekend in June would have to wait. Staying positive would be a chore, and progress would be measured in neighborhood walking loops instead of multi-hour singletrack adventures.

I also knew progress wouldn’t be linear.

It’s a stubborn fact I’ve confronted again these past two weeks. But let me back up.

The zero-mileage weeks right after the sprain were tough in a hobble-around-the-house kind of way. Mentally, they were also surprisingly manageable. I didn’t have a choice. My mangled foot dictated whether I’d walk outside, when I’d be ready to go around the block, and when running might be possible. The choice was made for me.

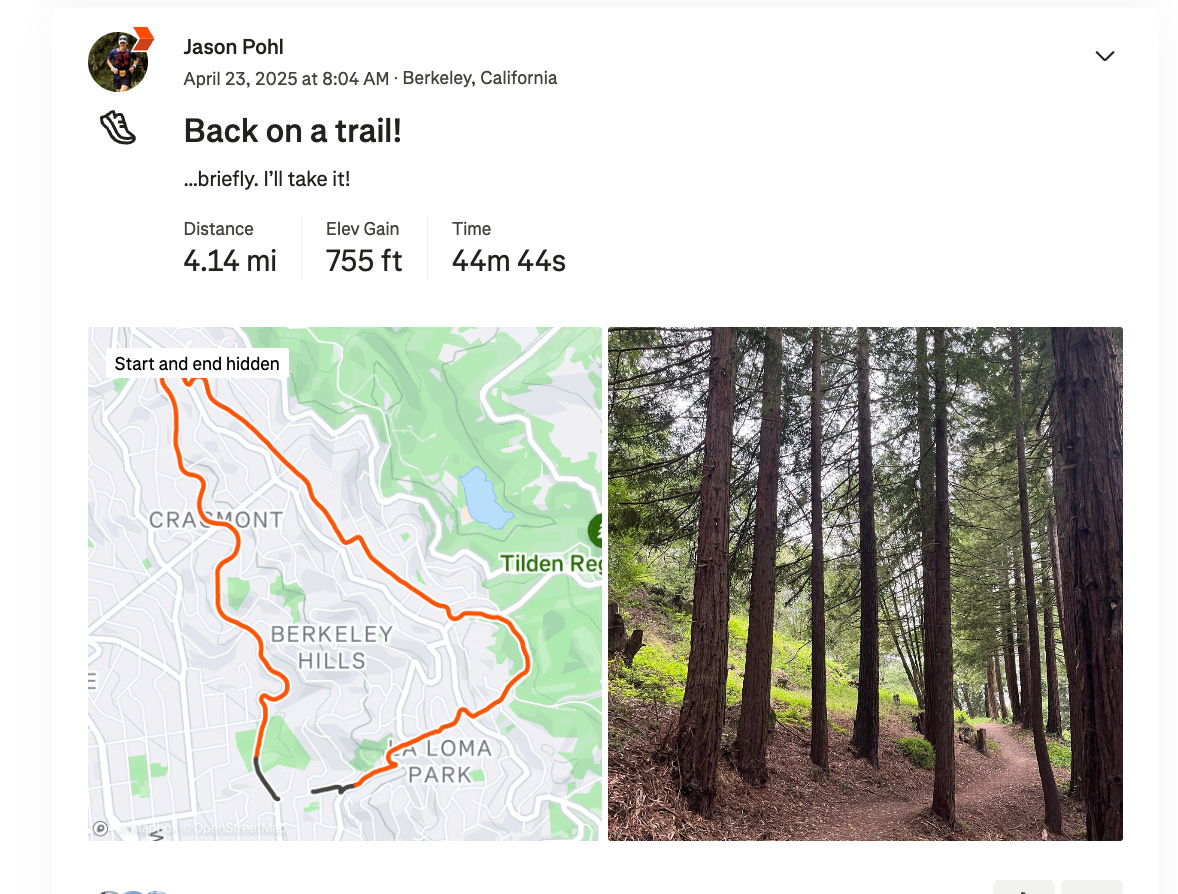

Gradually, I was able to phase in short neighborhood walks. Easy indoor biking came a few days later. Then indoor bike workouts that generated decent power through my legs.

But in what feels like no time now, I was trotting neighborhood loops. I overdid it some days, and a sharp pain or dull ache quickly reminded me to slow my roll. By week four, the swelling and bruising had mostly gone. By weeks five and six, I was back running easy onto smooth fire roads, celebrating the little joys of ditching the brace and beginning to feel strong again.

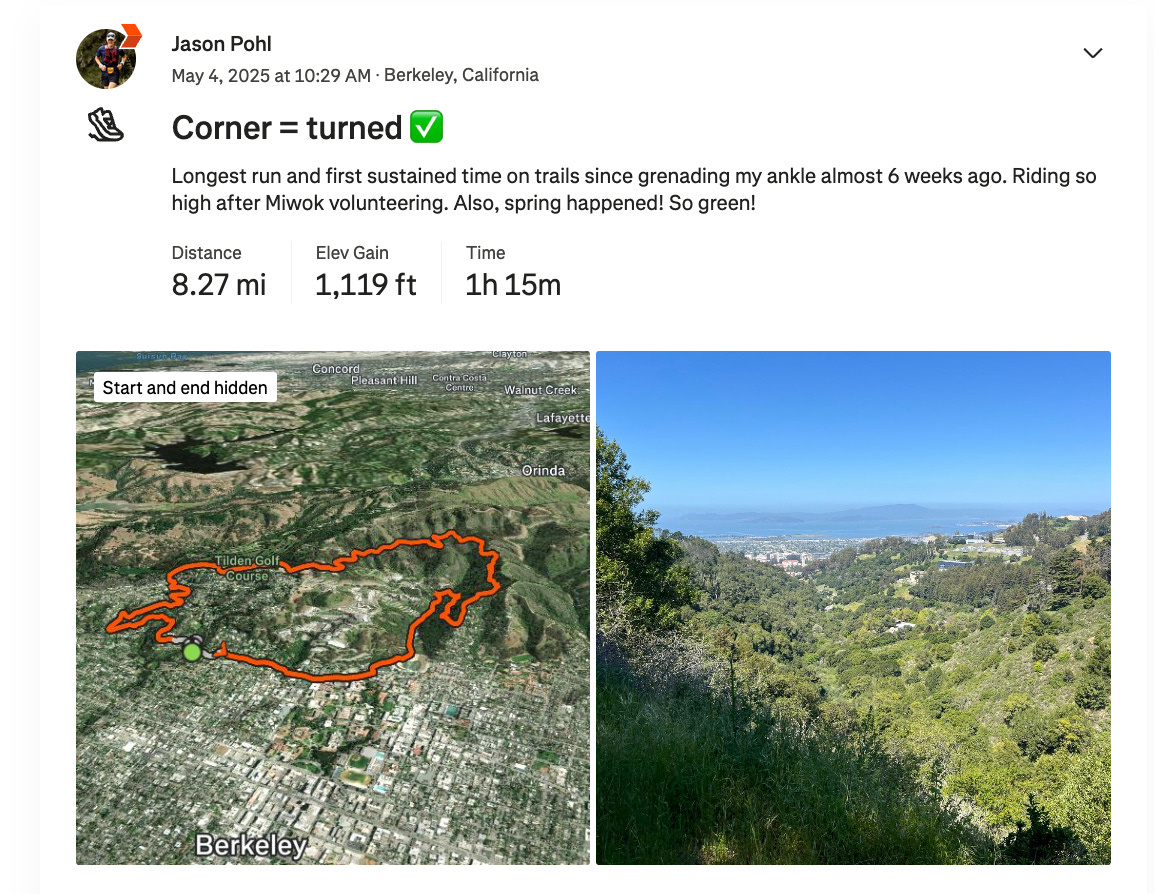

I’d hoped to be strong enough to run the Miwok 100k, but that wasn’t in the cards. Instead, I signed up to volunteer, a decision I second-guessed immediately after committing. I was worried being at the finish line would be a frustrating reminder of my own derailed spring training plans. This was silly in hindsight; the community vibes were fantastic, and it made me remember there’s more to this sport than running our own races. Driving home around midnight, I thought how a prior version of myself would have felt a stinging sense of failure for not at least lining up and seeing how far I could go. It was absolutely the right call not to. No regrets.

I read more books with the added downtime. I lived vicariously through my athletes’ spring races. And I joined a gym. It was my first time having a membership since March 2020, and I was finally reacquainted with the weird fitness wonders of an uphill treadmill cranked at 15%.

Mostly, I signed up so I could broil myself in a sauna and compel my body to like the heat (or dislike it less). While sitting in that 10x10-foot room, pouring sweat during an eight-day acclimation protocol, my brain started to feel real hope again about Western States. Excitement even.

A 10-miler in the Marin Headlands went great. So did an uphill interval session a few days later. My sprained ankle continues to improve. Some stiffness is still there, as is some swelling and Achilles and calf tightness. This is all manageable and expected

But then came the curveball.

Bodies have a way of reminding us of their imperfections. Even on a good day, my ankles have plenty. Where bones in the joint are supposed to glide past one another, my talus and calcaneus are basically bonded together. Thanks to a genetic fluke called a tarsal coalition that affects about 1% of the population, I don’t have the normal range of motion and have to work aggressively to keep my ankles from becoming rigid. A doctor years ago told me most people don’t notice the condition because they’re not running distances where the issues show up. (One side effect of the ankle sprain is that I learned via x-ray that my right ankle — my “good” one! — has the same problem. About half of people with a coalition in one have it in both. Lucky me!)

Throughout the ankle sprain, I’d worked to keep strength and motion up in my historically bad ankle, which was now my good ankle. But the reduced running inevitably set things back. A return to hills seems to have flared up tendons right in the area of that bone spur.

Translation: Reduced running, again.

I can bike mostly pain-free. The tendons calmed a bit last weekend, and I was able to do 13 miles on Sunday. I’ve biked, lifted and broiled this week. I’m hopeful doctors might have some suggestions next week on additional short-term solutions.

This three-week period is arguably the most important for 100-mile races. It’s where runners often stack their biggest mileage and run their steepest downhills to get the eccentric muscle contractions needed for race day.

That’s obviously a nonstarter. And it’s causing a lot of doubts. Again.

Injuries suck. Nonlinear recoveries suck. The snuffing out of flickers of hope sucks.

But I’m trying to remind myself of the joy that came from the community vibes at Miwok. I’m channeling the experiences of the athletes I coach. And as I’m cooking in the sauna next to an uncomfortably loud, naked man doing deep-breathing exercises, I’m trying to channel the excitement and hope again. The flipside of nonlinear recovery is exponential growth, after all.

I’ve thrown aside most of my performance goals for States. I’ll be ecstatic if I’m able to cross the finish line on the track.

Just lining up in five weeks will feel like its own kind of finish.